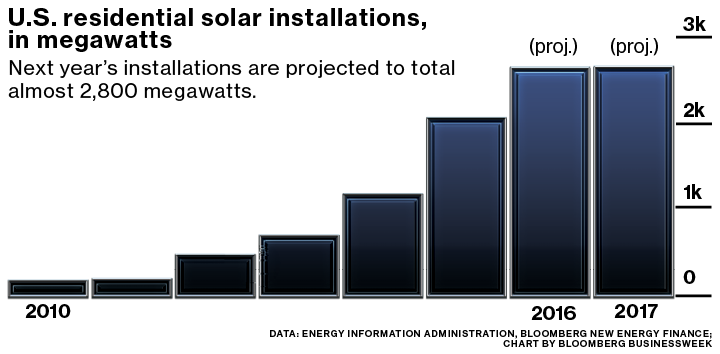

This was supposed to be solar’s moment. Residential panel installations in the U.S. grew 71 percent in 2015 as the falling cost of panels made the power they generate more competitive. In December, Congress unexpectedly extended a tax credit set to expire at the end of 2016. Panel buyers will get reimbursed for 30 percent of the cost of new solar panels through 2019 and at least 22 percent through 2021.

Yet instead of energizing the industry, the extension has hurt growth, as solar companies no longer rush to meet a deadline. After jumping more than 1,000 percent since 2010, panel installations are projected to grow by only 0.3 percent in 2017, according to Bloomberg New Energy Finance. Faced with the industry’s first major slowdown, companies are figuring out their next move. “You’re selling the urgency to get in while the tax credits are available,” says Hugh Bromley, an analyst at BNEF. “Once you have long-term subsidy certainty, solar companies may struggle to reimagine their sales pitches.”

Falling power prices in some markets don’t help. Consumers looking to lower their bill might not get the savings they used to by installing a solar system. There’s also doubt over net-metering laws that require utilities to pay rooftop customers for the power they sell to the grid. Although 43 states have some version of net metering, according to BNEF, last year Nevada, one of the fastest-growing states for solar, added a fee for homes with panels and cut the amount utilities pay them for the power they add to the grid. The two top U.S. panel installers, Elon Musk’s SolarCity and Sunrun, promptly left the state, which in September agreed to grandfather prior rates for 32,000 existing customers.

Investors are demanding a reset of solar’s business model. “It was growth at all costs,” says Michael Morosi, an analyst at Avondale Partners. Now that the market isn’t paying for that growth, companies can “go for the most profitable customers,” he says. Solar companies have long relied on a leasing model, signing homeowners to 20-year contracts that require no money down. This ensured growth, but it also spread out revenue over decades. Now, solar companies are selling more units, which ensures they get paid sooner.

For SolarCity, the country’s top installer, cash sales and loan payments accounted for more than 30 percent of revenue in September, up from about 20 percent in the second quarter, says Chief Executive Officer Lyndon Rive. Leasing is expected to account for less than half of new installations in 2017, down from more than 70 percent in 2014. This is a mark of maturity for the $7.8 billion U.S. residential solar industry, says Benjamin Cohen, chairman of renewable-energy financing company T-Rex. “Installers can focus on what is the most efficient use of their balance sheet,” he says. “Maybe this moment says these companies shouldn’t be behemoths.”

Growth should resume by 2018, BNEF says. Only 1 percent of U.S. households have panels on their roofs. “Every other solar market during its period of retooling has faced a collapse of 20 to 90 percent,” says BNEF’s Bromley. “So for the U.S. to face a year or two of stagnation before continued growth is an overwhelmingly positive outcome.”